featured work: insights

What the Paris Agreement means for Carbon Pricing and Natural Climate Solutions: A Business Guide

Client: The Nature Conservancy

Engagement - insights

In mid 2018 Anthropocene was engaged by The Nature Conservancy to write a paper, intended to help businesses seeking to support natural climate solutions via carbon finance, to navigate the emerging landscape of carbon offsetting under the Paris Climate Agreement.

process

Working alongside Christopher Webb (Director, Climate Markets TNC Europe), and through consultations with Conservancy team members, industry participants and policy makers, a detailed analysis was carried out which identifies a new landscape for business engagement under the Paris Climate Agreement.

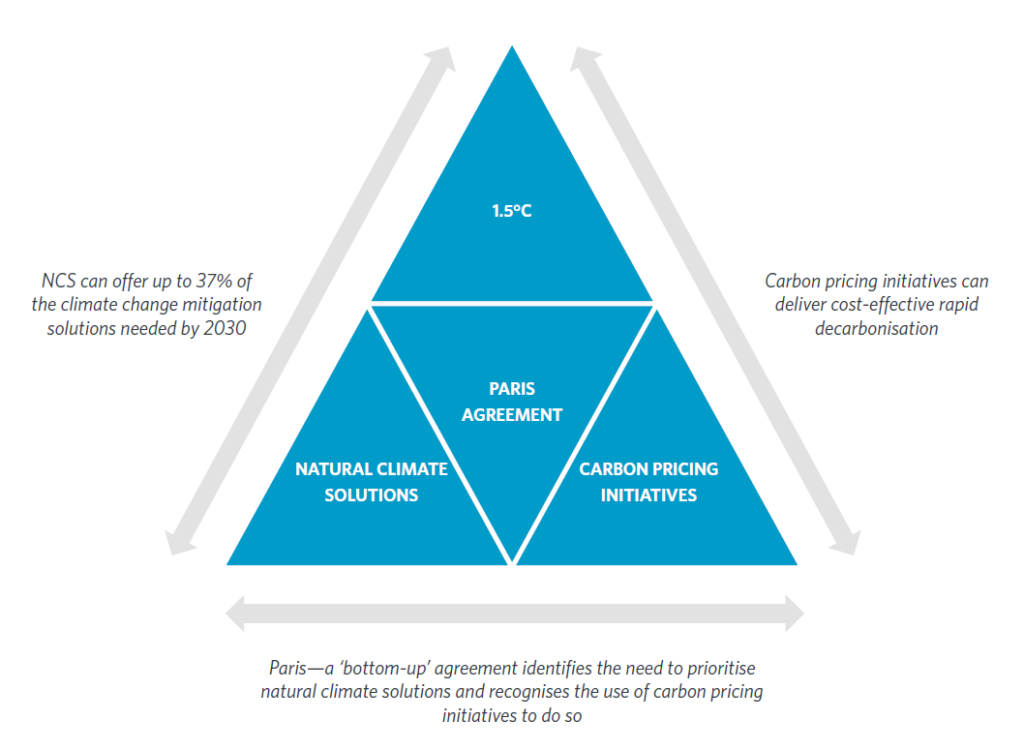

The paper sets out the case for Natural Climate Solutions, the role and potential of carbon pricing solutions to deliver finance and how carbon markets, as envisioned under the Paris Agreement may be able to facilitate such engagement.

Result

Published in 2019, the paper sets out the potential for ‘natural climate solutions’ to make a much greater contribution to corporate and governmental efforts to address global warming, and the role of carbon pricing initiatives in doing so. In the context of the changes and uncertainties created by the Paris Climate Change Agreement, it also suggests three key steps business can take to maximise these opportunities as part of robust corporate ambition and action on tackling climate change.

1. Adopt a robust and comprehensive climate strategy

2. Support strong public policies

3. Invest to learn and lead

Download

Introduction

“Rapid, far-reaching and unprecedented changes in all aspects of society.”

The 2018 Special Report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) was emphatically clear that we have a limited window, perhaps 10-20 years, to avoid the worst impacts of climate change, but only if we start taking much stronger steps immediately.

As shocking as these findings have been for many, as surprising is that the world already has at its disposal some necessary, affordable ingredients to respond to the climate change threat.

This includes the Paris agreement, which was negotiated by Parties (countries) to the United National Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) as the successor to the Kyoto Protocol (which runs to 2020). The Paris Agreement was finalised in late 2015 and has since been ratified by 183 countries, entering into force as a triumph of international diplomacy and a clear sign of governments’ recognising the need for urgent action on climate change.

Robust multilateral support for the Paris Agreement was due, in part, to countries abandoning some of the Kyoto Protocol’s

approaches to governance, while increasing accountability. Unlike Kyoto, which only included emission reduction targets for rich countries, the Paris Agreement encourages all countries to make contributions to climate change mitigation. And, unlike Kyoto, where rich countries mutually agreed to their respective share of contributions, under the Paris Agreement countries independently decide on the extent (and ambition) of their contributions, as contained in their Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) submissions.

Countries will deliver on these NDCs through any number and type of domestic interventions—including implementing public policies and attracting private investments in low-carbon solutions.

The Paris Agreement’s bottom-up approach has brought a significantly larger number of countries to the table, including developing countries that proposed targets for emissions reductions for the first time, and outlined (to varying degrees of detail) the policies and measures they would introduce to meet them. On the flip side, the departure from the Kyoto Protocol’s centralised, ‘single-rule-set’ approach to international emissions trading, blurs what was once a clear and common framework for carbon markets and market-based finance.

In this context, the landscape for carbon finance, corporate investment in climate solutions, and land sector offsets—the focus of this paper—will also necessarily change. It will be vitally important for companies wishing to navigate the low-carbon transition, and maximise the related business opportunities that will emerge, to properly understand this landscape and engage with critical stakeholders.

This paper sets out the potential for ‘natural climate solutions’ to make a much greater contribution to corporate and governmental efforts to address global warming, and the role of carbon pricing initiatives in doing so. In the context of the changes and uncertainties created by the Paris Climate Change Agreement, it also suggests three key steps business can take to maximise these opportunities as part of robust corporate ambition and action on tackling climate change.

Natural climate solutions can provide up to

Carbon pricing initiatives

Carbon Pricing Revenues raised

What are natural climate solutions?

(Section 2, Page 9)

Natural climate solutions are activities that enhance or protect natural systems such as forests, grasslands. Examples include:

1. Better farming practices which have the potential to reduce carbon emissions associated with feeding the global population, while increasing food security.

2. Protecting forests and grasslands from conversion to other uses, which can avoid the release of stored carbon, while increased tree planting has the potential to remove carbon present in the atmosphere.

3. Protecting or restoring coastal wetlands, which can both avoid carbon emissions and help protect coastal areas from flooding.

What is carbon pricing?

(Section 3, Page 14)

Carbon pricing initiatives apply a cost to greenhouse gases emitted into the atmosphere, providing an economic incentive for those emissions to be reduced or avoided (see Table 1). They can also involve a (declining) cap on the total emissions permitted or be applied voluntarily by businesses operating outside of a capped sector.

• Carbon pricing assigns a cost to the right to emit carbon and encourages actors to respond to the risks of climate change.

• Carbon pricing initiatives are favoured as a cost-effective policy tool for their ability to lower the costs of reducing carbon emissions, through decentralising (in part) decisions on where it is most efficient to reduce emissions from government to business and stimulating

innovation by providing an ongoing incentive to cut carbon 11.

• Such factors which increase confidence amongst both government and business that lower-cost reductions are accessible, can in turn be a powerful lever to greatly increase ambition to tackle climate change Indeed, recent analysis suggests that with international carbon pricing and trading, it is possible to nearly double the climate ambition at the same overall cost as countries’ complying with their Paris Agreement targets.

• Whilst, there is also some evidence that companies that use offsets have gone significantly further in reducing their own carbon footprint then those who do not.

• Carbon pricing initiatives are being utilised by governments at national (e.g. China), sub-national (e.g. California), and sectoral levels (e.g. aviation), and are implemented by some businesses internally, voluntarily ahead of regulation.

• National, regional and sub-national governments have fifty-three such carbon pricing initiatives (emission trading systems and carbon taxes), at various stages of implementation, covering 20% of all global greenhouse gas emissions.

The Paris Climate Agreement introduces a new landscape for business engagement

(Section 4, Page 20)

The Paris Agreement allows countries to make use of international carbon markets, including land-use sector offsets, in meeting their nationally determined goals. But whereas the Kyoto Protocol operated under a single framework, which set the rules dictating how carbon credits could be created, traded and tracked, rules under the Paris Agreement, (yet to be agreed), are expected to be less prescriptive, in line with the principle of ‘bottom-up’ implementation.

Indeed, the Paris Agreement itself allows individual countries the ability to define domestically and between one-another much of their own rules. This opens-up enormous opportunities for offset projects and carbon pricing initiatives tailored to national requirements, but it also requires market participants to navigate potentially different systems across countries.